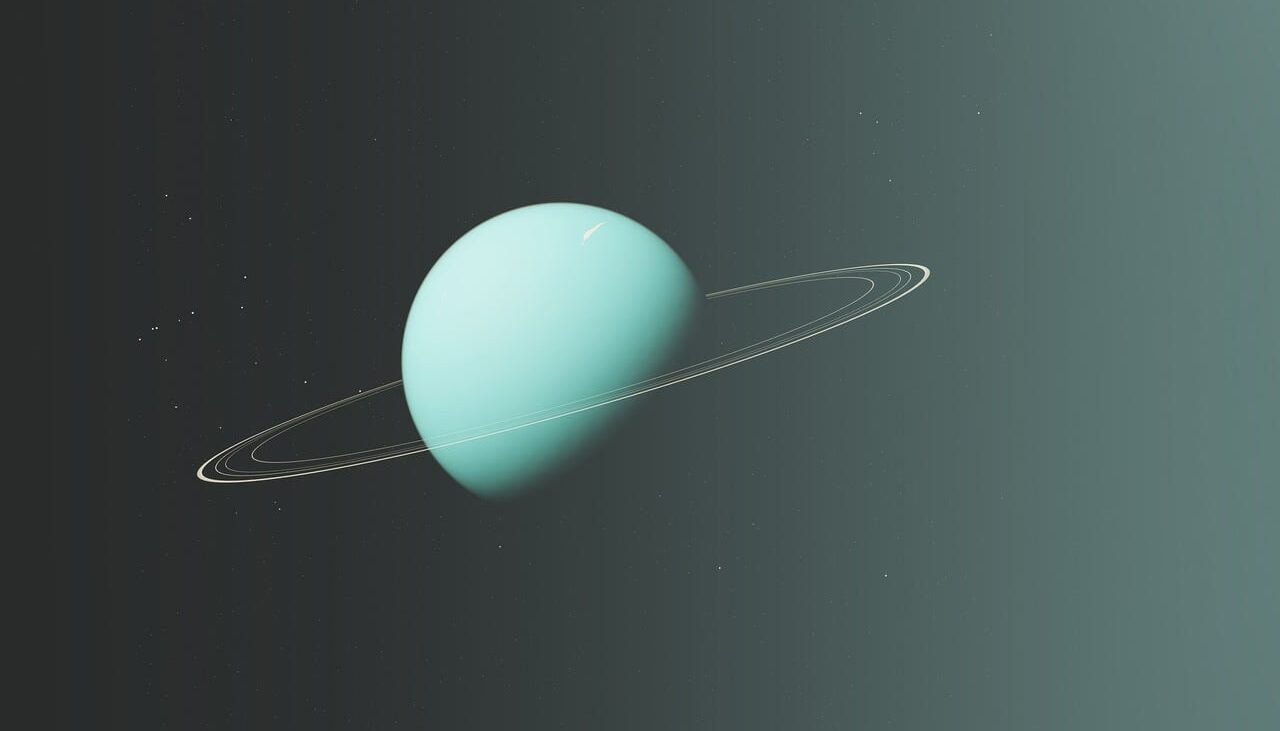

If the solar system hosted a talent show for “Most Unconventional Planet,” Uranus would cartwheel onto the stage and steal the spotlight. This pastel-blue ice giant orbits on its side like a rolling ball, flaunts jet-black rings you can barely see, and whips up winds faster than Earth’s fiercest hurricanes—all while chilling at temperatures cold enough to freeze hydrogen.

With NASA and international space agencies lining up new missions to probe its secrets in the 2030s, now’s the perfect moment to brush up on what makes this sideways spinner so extraordinary.

Dive into 60 bite-size facts that reveal why Uranus isn’t just the butt of planetary jokes—it’s one of the most mind-bending worlds we’ve ever discovered.

- Uranus orbits the Sun once every 84 Earth years, so a child born during Voyager 2’s 1986 flyby will be pushing retirement before the next full Uranian “year” is up.

- A day on Uranus is short—about 17 hours—but the planet spins retrograde, opposite most planets, and lies on its side at 98° tilt, so its poles take turns staring at the Sun.

- Because of that extreme tilt, each pole gets 21 straight Earth years of sunlight followed by 21 years of darkness, creating the strangest “seasons” in the solar system.

- Uranus and Neptune are called ice giants because their interiors contain slushy “ices” of water, ammonia, and methane—though they’re hot enough inside to melt lead.

- The blue-green hue comes from methane gas, which absorbs red light and scatters blue; trace hazes at cloud tops fine-tune the exact aquamarine shade visible through telescopes.

- Uranus holds the record for coldest atmosphere of any planet: –371 °F (–224 °C) at the cloud tops, colder than Neptune despite being a bit closer to the Sun.

- Discovered in 1781 by William Herschel, Uranus was the first planet found with a telescope, overturning ancient notions that only six planets existed.

- Herschel wanted to name it Georgium Sidus after King George III, but astronomers later agreed on Uranus, the Greek sky god (and father of Saturn).

- Uranus’s mass is about 14½ Earths, yet its radius is only four times ours, meaning gravity at the cloud tops pulls with roughly 90 % of Earth’s surface gravity.

- Voyager 2, launched in 1977, is still the only spacecraft ever to visit Uranus; it flew by on 24 January 1986, snapping 7,000 photos and discovering new moons.

- During that flyby, Voyager measured wind speeds topping 560 mph (900 km/h) at mid-latitudes, blowing westward while the poles rotate almost as calm oases.

- Uranian rings weren’t seen until 1977 when astronomers watched a star blink several times—proof the planet sports at least 13 dark, narrow rings made of dusty ice.

- The brightest ring, epsilon, is no wider than 60 miles but extremely dense; its particles range from golf-ball pebbles to boulders the size of buses.

- Unlike Saturn’s glittering rings, Uranus’s rings are jet-black, reflecting just a few percent of incoming sunlight—nearly invisible to backyard scopes.

- Uranus has 27 known moons, all named for Shakespearean and Alexander Pope characters; no other planet honors literature so thoroughly.

- The five major moons—Titania, Oberon, Umbriel, Ariel, and Miranda—span 300–980 miles across and may hide subterranean oceans of ammonia-water slush.

- Miranda, the smallest big moon, looks like a patchwork quilt of cliffs and canyons; scientists joke it resembles a cosmic “Frankenstein” built from spare parts.

- One cliff on Miranda, Verona Rupes, is up to 12 miles high—the tallest known scarp in the solar system—so a rock dropped from the top would fall for 10 minutes.

- Uranus’s magnetic field is wildly off-center: its dipole is tilted 59° from the rotation axis and offset by one-third of the planet’s radius, causing lopsided auroras.

- Those auroras were first caught from Earth by the Hubble Space Telescope, glowing in ultraviolet as the solar wind slams into Uranus’s skewed magnetosphere.

- Scientists think a giant protoplanet slammed into Uranus early on, knocking it sideways and possibly creating molten pools that became its moons and rings.

- Uranus’s rotation may cause “magnetospheric flip-flops” every half-orbit, as the north magnetic pole alternates between pointing toward and away from the Sun.

- Despite frigid cloud tops, deep inside Uranus reaches an estimated 9,000 °F (similar to Earth’s core); heat fails to rise efficiently, explaining its cold outer layers.

- Laboratory shock-compression of water-ammonia mixtures suggests exotic superionic ice forms inside Uranus—part solid lattice, part liquid—conducting electricity.

- In 2020, researchers modeled that diamonds could rain down in Uranus’s mantle, forming kilometer-scale diamond “bergs” floating in a sea of carbon and ice.

- Uranus emits far less internal heat than Neptune, a puzzle dubbed the “Uranus chill”—no one knows why its heat flow appears strangely throttled.

- From Earth with good binoculars, Uranus looks like a faint aquamarine dot; professional scopes tease out fleeting white storms across its cloud deck.

- Time-lapse Keck and Hubble images in 2014 captured a huge bright storm near the equator, sparking talk of Uranus waking from a decades-long atmospheric slumber.

- Like Saturn, Uranus experiences seasonal methane-ice clouds that whiten its polar caps; these evolve slowly given the 21-year sunlight cycles.

- At solstice in 1986, Voyager saw the south pole squarely lit; when the next solstice arrives in 2028, telescopes will shine on the north pole for the first close look.

- Uranian “hours” can’t be set by sunrise; instead, planetary scientists define coordinates using radio bursts tied to the magnetic field’s rotation.

- Sunlight at Uranus is only 1/400th as bright as on Earth, so noon looks like dim twilight; yet solar panels still work—NASA tested prototypes for far-future missions.

- NASA’s proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP), recommended by the 2023 Decadal Survey, could launch in the early 2030s and arrive mid-2040s.

- That mission would deploy an atmospheric entry probe to sniff noble gases, solving mysteries about how ice giants differ from gas giants like Jupiter.

- Uranus’s Hill sphere (the region where it dominates gravity) spans 41 million miles, large enough to fit Saturn’s entire orbit around the Sun within it.

- Every 42 years, Uranus’s ring plane aligns edge-on to Earth; stellar occultations then let astronomers weigh ring particles and discover new moonlets.

- Ariel shows fresh, bright canyon systems, suggesting cryovolcanic resurfacing within the last 100 million years—recent by solar-system standards.

- Umbriel, conversely, is dark and ancient, with a mysterious bright ringed crater dubbed “Flan” that stands out like a cosmic bullseye.

- Titania sports fault valleys up to 1,000 miles long, evidence the moon expanded as its interior slowly froze, cracking the icy crust.

- Oberon has mountains likely formed by ancient impacts lifting crustal blocks; some peaks rise more than 4 miles above the surrounding plains.

- In the outer solar system, seasonal haze may condense hydrocarbons; JWST’s 2022 observations revealed Uranus’s north pole developing thicker photochemical smog.

- While Jupiter’s Great Red Spot rages for centuries, Uranian storms seem transient, flaring during seasonal shifts when sunlight creeps toward a pole.

- Uranus is the dimmest naked-eye planet; sailors in the 1700s mistook it for a star—Herschel at first labeled it “a curious comet” before orbital math proved otherwise.

- The planet’s ring particles are thought to be young—maybe only 600 million years old—possibly debris from shattered moons after a high-speed collision.

- Early telescope sketches nicknamed Uranus “the Georgian Planet” for decades in Britain; continental astronomers resisted, preferring mythological naming schemes.

- Some exoplanets discovered in other systems match Uranus’s size and temperature, so our ice giant serves as a local laboratory for studying distant worlds.

- Uranus’s obliquity may cause interior “seasonal tides,” sloshing its dense mantle and subtly altering rotation length over decades.

- If you could stand in Uranus’s upper clouds (in a heat-proof suit), the blue sky above would still look bright, while the Sun would appear as a small pale disk.

- Infrared spectra show hydrogen sulfide above Uranus’s clouds—the rotten-egg gas absent on Jupiter—suggesting different chemical layering during planet formation.

- Voyager 2 detected faint, bursty radio emissions called UEDs (Uranian Electrostatic Discharges), likely lightning in storm clouds deep below the haze.

- Because Uranus’s rings and equator are tipped, its moons orbit like a giant bullseye, giving spacecraft complex navigation challenges for future flybys.

- Uranus likely formed closer to the Sun, migrating outward during early solar-system chaos; its sideways tilt may record violent rearrangements that sculpted all outer planets.

- At perihelion (closest to the Sun) Uranus coasts at 1.7 billion miles; at aphelion (farthest) it drifts 115 million miles farther out—seasons and distance sync in odd ways.

- Micro-seismic “ring seismology” could one day read oscillations in the rings to probe Uranus’s internal structure, much as Saturn’s rings reveal Saturn’s core.

- Uranus’s bulk density is 1.27 g/cc, only slightly heavier than water, so if you had a cosmic ocean big enough, the planet would (barely) float.

- The escape velocity at the cloud tops is 13,300 mph, meaning any rocket leaving Uranus needs half the power required to escape Earth.

- Ice-giant atmospheres might host “bergs” of solid hydrogen under extreme pressure—a strange state of matter being recreated in high-energy physics labs.

- Simulations show Uranus’s interior could generate helium rain, separating out heat—another reason why the outer envelope remains so chilly.

- Because of the 98° tilt, a compass on Uranus would be useless: magnetic north sometimes lies closer to the equator than the spin pole.

The next generation of telescopes—JWST, the Giant Magellan, and the Thirty Meter—will watch Uranus’s spring awaken now through the 2040s, giving Earth-bound observers front-row seats to a planet slowly turning its strange, pale face to the Sun once more.